Miniseries: The Oldest Rocks in Australia

Hello, and welcome to Bedrock, a podcast on Earth’s earliest history.

I’m your host, Dylan Wilmeth.

These next few weeks, I’m off on summer break, so we’re doing something different on the show. We’re going to take a quick tour around the Earth in seven weeks. Our destinations will be the oldest rocks on each continent. Seven weeks, seven continents.

These locations will be very important in upcoming seasons, so think of these episodes like teaser trailers. Hopefully when we’re all done, you’ll want to learn more. If you want to follow along at home, we’ll have geologic maps of each continent on our website: bedrockpodcast.com

The rocks on this series only cover 5% of the Earth’s surface, but represent the first half of Earth history. Some continents have a lot of ancient rocks, some very few. One contains the oldest fossils on Earth, and that is our destination for today. Break out your maps, it’s time to visit Australia.

***

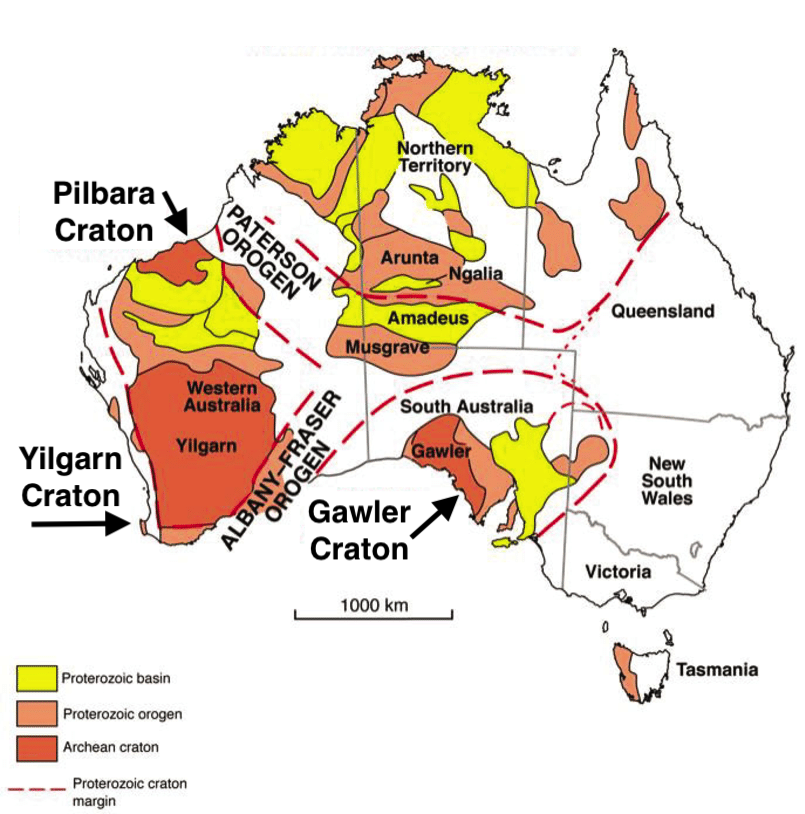

Precambrian rocks of Australia: Archean cratons in dark orange.

Australia is the smallest continent and the least populous after Antarctica, but it more than makes up for it in terms of age. Australia’s two biggest claims to fame are the oldest stuff on Earth, zircon crystals 4.4 billion years old, and the oldest fossils on Earth, fossil pond scum 3.5 billion years ago.

But before we dive into specifics, let’s start with the big picture. Unlike Antarctica, every inch of Australia has been mapped by geologists, since there aren’t any giant ice sheets in the way. Very broadly, Australia gets older the farther west you travel. If you live in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, or Tasmania, you could find dinosaurs or giant fossil salamanders the size of crocodiles, but these are newcomers in Earth history. If you live in Cairns, Darwin, or Alice Springs, we will eventually talk about rocks in your area, but not until Seasons 6 through 8, a long way from now.

The oldest rocks in Australia form three large patches across the continent: two in Western Australia, and one in South Australia. If you live near Perth, Adelaide, or Port Hedland, today’s your lucky day!

These large patches of Earth are called “cratons”. This is a word we will get to know well on the show. Cratons are simply the oldest parts of a continent- they form irregular blotches in random spots. The word craton comes from the ancient Greek god of strength and popular video game character, Kratos.

One ton coin of Yilgarn gold: National Mint, Perth.

We begin our journey with the oldest and largest Australian Craton, the Yilgarn Craton. The Yilgarn is one of the largest expanses of ancient rock in the world- it covers an area larger than France or Texas. It’s shaped like a large triangle nestled in the southern half of Western Australia. This makes Perth the closest major city to Australia’s oldest rocks. Perth is one of the most remote cities in the world: the closest city with more than 100,000 people is Adelaide, more than 2,000 km to the east. One of Perth’s lifelines is the local geology, most notably gold.

In the late 1800s, a series of gold rushes rocked the Yilgarn Craton and made Perth a major destination, growing from 8,000 to 60,000 in just twenty years. Mineral exploration continues to this day, and Western Australia has some of the best geology maps in the world. If not for gold and iron, it might have taken far longer to discover the scientific riches of these remote Australian cratons.

The Yilgarn Craton contains the oldest material in Australia and the world, the Jack Hills zircons, tiny crystals up to 4.4 billion years old, January 14th on the Earth Calendar. The only older items you can hold are meteorites. We’ve covered the Jack Hills and their stories in great detail, if you want to learn more, check out Episodes 10-16. In short, these crystals tell us tales of Earth’s earliest crust and oceans, just after the Moon formed.

Most of the Yilgarn Craton has been pressure-cooked over billions of years, just like the rocks we saw last week in Antarctica. For scientists like me who want to study the ancient Earth, this is a big bummer, since heat and pressure usually erase any traces of life and mess up original chemical signals. It’s like trying to tell how a car worked after it’s been compressed into a cube. There are one or two places to find fossil pond scum, but they are not well-studied.

On the other hand, the same pressure cooking also delivered the gold and other precious minerals which laid the foundation for years of geology research, so it’s a mixed blessing.

The next Australian craton has the best of both worlds: like the Yilgarn, it is incredibly mineral-rich, especially in iron ore. Even better, this area contains the most well-preserved rocks of their age. This is the Pilbara Craton, and it will be one of the two major locations for Seasons 3 though 5.

The Pilbara Craton is directly north of the Yilgarn, on Australia’s northwest coast. The largest towns are Karratha and Port Hedland on the Indian Ocean, 15,000 people each compared with Perth’s two million. Already you can tell how remote these rocks are. And yet, there have been hundreds of papers from the area over the past sixty years, and it’s where I’m doing fieldwork in a few weeks.

The Pilbara region has taught geologists so much about early oceans, plate tectonics, volcanoes and other topics. But arguably, the most influential area of Pilbara research has been ancient life. Then again, I study ancient life, so I might be biased.

Stromatolite. 3.5 billion years old, Pilbara Craton

The oldest fossils on planet Earth are in the heart of the Pilbara Craton, in rocks 3.5 billion years old, late March on the Earth Calendar. The rocks are called the Dresser Formation. If I showed you these rocks, you would see interesting patterns, but they would not immediately look like fossils. There are no bones, leaves, or footprints this old.

Instead, you would see a shape that looks like fossil lasagna or cabbages, with many wrinkled layers stacked on top of each other. Each layer used to be a colony of bacteria sitting at the bottom of an ocean or pond- this is the ancient primordial ooze that everyone keeps talking about. Over time, this colony was turned to stone, and a new layer of microbes formed on top. Rinse and repeat.

These fossils are called stromatolites, which literally translates to “layered rock” in ancient Greek. Stromatolites, or stroms for short, are the oldest fossils on Earth, and for most of prehistory, they are the only fossils we can see with the naked eye. Dinosaurs are great, mammoths are cool, but for three billion years, Earth was the planet of the stromatolite.

If you can’t tell already, stromatolites are my scientific passion.

You can point anywhere on a map of the Pilbara, and you will probably find a fossil strom in a few kilometers. Most are younger than the Dresser Formation, closer to May or June on the Earth Calendar. Some formed in the sea, others formed in giant lakes, and some like the Dresser, formed in hot springs just like Yellowstone, Iceland, or New Zealand. Visit these places today, and you will see colorful mats of pond scum, slowly turning into stone just as they did 3.5 billion years ago.

I can wax poetic about stroms all day long, but we’ll learn much more in the future. The important takeaway is that the Pilbara Craton in northwestern Australia is one of the most important spots to study ancient Earth, especially ancient life. If you want to learn more, check out my recent interview with Dr. Joti Rouillard on bacteria fossils from the Pilbara.

The last craton on our tour is in the heart of South Australia, stretching from Adelaide in the south up through the Barossa wine country into mines in the Outback such as Coober Pedy and Peculiar Knob. This is the Gawler Craton. As with the Yilgarn and the Pilbara, the Gawler mines are incredibly important to the region and for geologists.

The oldest rocks in the Gawler Craton are in the Eyre Peninsula on the south coast, close to Whyalla and Port Augusta. These granites are 3.2 billion years old, mid-April on the Calendar, but for our final stop, let’s look at some mines next door.

Banded iron formation, Gawler Craton, 1.9 billion years old

With names like the Iron Duchess, the Iron Magnet, and the Iron Knob, you can quickly guess what these miners are looking for. This iron ore is about half the age of the Earth, 2.5 billion years old. These rocks have beautiful tiger-striped patterns of rusty iron and black silicon. Geologists call them Banded Iron Formations, or BIFs for short. Many of the largest iron mines in the world are sitting on top of BIFs, and many of those BIFs are about 2.5 billion years old.

Clearly something big happened in Earth’s middle ages, something that made the oceans rust. Just like today, that thing was oxygen. For 90% of Earth’s history, there was almost no oxygen in the air or water, and we would need space suits just to breathe. Even small whiffs of oxygen had a big impact on the world back then, producing most of the iron ore we mine today.

Today, oxygen comes from plants and plankton, but back then, it was bacteria. Once again, we see the importance of stromatolites. Oxygen from bacteria turned ancient iron into rust, which was mined billions of years later by humans. That iron ore is shipped around the world and turned into steel for cars, planes, and trains- vehicles that can take you to Australia, or anywhere you’d like to go. Everything is connected to the ancient world.

Speaking of travel, it’s time to brush the rust off our boots and hit the road again. Don’t worry, Australia will be a frequent destination in future seasons. There’s only one place on Earth that will give it a run for its’ money. Next week, we’ll see ancient riverbeds filled with uranium and even more fossil bacteria as we tour the oldest rocks in Africa.

***

Thank you for listening to Bedrock, a part of Be Giants Media.

If you like what you’ve heard today, please take a second to rate our show wherever you tune in- just a simple click of the stars, no words needed unless you feel like it. If just one person rates the show every week or tells a friend, that makes us more visible to other curious folks. It always makes my day, and that one person could be you. You can drop me a line at bedrock.mailbox@gmail.com. See you next time!

Images:

Australia Craton Map: modified from Garcia-Alvarez et al., 2014, originally from Smithies et al., 2011

One Ton Coin: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Perth_Mint_-_Joy_of_Museums_-_The_One_Tonne_Gold_Coin.jpg

Stromatolite: personal photo

BIF: https://www.flickr.com/photos/jsjgeology/15059380105

Music: