34: Bombardment

Episode 34: Bombardment

It’s been a while since we checked in on the moon- 25 episodes, to be exact!

We last left our lunar neighbor in Season 1, 4.5 billion years ago. On our imaginary Earth Calendar, that was the first week of January. In Season 2, we’re now on the first week of March, 3.8 billion years ago.

In that time, we’ve met Earth’s oldest minerals, rocks, oceans, and life. All that time, the Moon has been watching from above. But it is not the Moon we know and love.

In Season 1, the Moon was molten hot and frighteningly close, the size of your fist in the night sky. Since then, it’s backed off a bit- just the size of two fingers at arms’ length, but still more than twice the size we see today.

The moon’s surface was also noticeably different. Today, we see vast dark circles surrounded by pale gray: the Man in the Moon. But 3.8 billion years ago, there was no Man in the Moon. The Moon was more like a golf ball- lots of craters, but no giant black eyes.

Today, that begins to change. The Man in the Moon didn’t form all at once- it won’t be complete until Season 3, but we’ll lay the foundations in this episode and the next. Or more accurately, we’ll do some demolition.

Part 1: Stories and Science

Before we learn how the Man in the Moon actually formed, I thought it would be fun to hear some very early guesses. In other words: mythology. To us, these stories might sound fanciful, silly, a superstitious time that we no longer live in. But to be fair, those ancient humans were asking the same questions we are on this show.

“How did the moon get there? Why does it have uneven patterns? What influence does it have in my life?”

Back then, there was no way to test these questions, no way to collect data. So folks made their best guesses. Today, we call those guesses “myths”, but you can learn a lot about a culture by the way they view the moon. For this section, I’d recommend having a picture of the moon out to follow along- we’ll have one on our website, bedrockpodcast.com.

In most Western cultures, the Man in the Moon is a giant face, with two huge craters for eyes, and some lumpy dark plains for cheeks and lips. But others see a whole person standing up there. Old Germans saw a man carrying a bundle of wood- with two small dark legs stretching to the upper right. Others see a pale woman’s head in the lower right corner, facing left, with a shock of dark hair and a bright crater for a necklace. In a Midsummer Night’s Dream, Shakespeare saw an old man with a lantern.

Apart from humans, the most common creature seen on the Moon is a rabbit, with two long dark ears stretching to the right. Cultures as far flung as China and the Aztecs in Mexico all saw giant rabbits. The next time you look, you’ll probably see the bunny yourself.

When people see a giant image in the sky, whether human or hare, they just have to make a story about it. There are too many myths to share in one episode, but there are a few themes.

In most, the human on the moon was forced there either by accident or by angering the gods. A Chinese woman named Chang’e was forced to take an immortality potion without her husband and fled to the moon in grief. In the American Northwest, a boy from the Haida nation was snatched up by the moon after complaining about chores. Finally, in east Europe, a Latvian lady, well, “mooned” the moon, which made sure everyone else could see, too, if you catch my drift.

If you have your own legend, send it my way to bedrock.mailbox@gmail.com. I might include it in a future episode, since we’ll keep talking about the moon next episode.

Back to geology.

In 1651, an Italian priest named Giovanni Riccioli (REE-cho-lee) stared up through a telescope, and labeled lunar features as if they were geographic locations, not mythical people. Riccioli called the dark areas “seas”, using the Latin word “mare”: Mare Imbrium, Mare Nectaris, and Mare Tranquilitatus, the Sea of Showers, the Sea of Nectar, and most famously, the Sea of Tranquility, where Apollo 11 landed.

Riccioli labeled more than 200 features on the moon, most of which we still use. We now know there’s no liquid water on the moon, but his names have stuck. To this day, we call the dark, flat plains “maria”, the plural form of “mare”. Again, that’s MAria, not maREEa like a person’s name.

The other major feature of the moon are the pale highlands, the areas between the low, dark maria. The highlands are the moon’s original face of the moon, the first surface that cooled down way back in Season 1. I’ve described this surface like a golf ball- white and full of craters. These craters range in scale from nearly invisible to the size of the Arctic Ocean, some of the largest in our Solar System.

Many of the Moon’s largest craters are filled with dark maria, which brings us full circle. What is the “Man in the Moon”? A series of titanic craters filled in with dark rocks we call maria. Today, we’ll learn about the ancient craters themselves, before they got filled in. Next episode, we’ll focus on those newer dark seas of stone.

Part 2: The Lunatic Asylum

If Season 1 had a mascot, it would certainly be an asteroid.

Our story started with two asteroids in Episode 4, with trillions of their siblings building the planet over time. Asteroids and comets also brought tiny ice crystals which melted, bit by bit, into the oceans. Finally, asteroids delivered carbon atoms, and even some complex organic molecules, to Earth’s surface. They likely did NOT bring life themselves, BUT they brought the building blocks to make it here, on our world. From small things, big things grow.

Carl Sagan said that we’re “star stuff”, and while he’s right, I would also make a case that we’re asteroid stuff. The stars make stuff, but the asteroids deliver it and build it.

But, asteroids, comets, and their cousins are double-edged swords. Remember, in Season 1 the Solar System was a terrifying place to be: a cosmic shotgun gallery with millions of objects flying around, hitting each other. A rogue planet the size of Mars devastated Earth, but made the Moon in the same stroke. There was creation and destruction in equal measure.

In the modern day, asteroid impacts spark more fear than joy, more destruction than creation. These space rocks were once our oldest, closest friends, but are now implacable enemies, a Sword of Damocles hanging over the planet.

Fortunately, our modern Solar System is a lot less crowded than those early days. Broadly speaking, the number and size of collisions has decreased over time in a nice smooth line.

Except, maybe, for one interesting hiccup, which brings us back to the moon.

Gerald Wasserburg, from Ann. Rev. Earth & Env. Sci., 2003

The year is 1974, five years after the first man on the moon, and two years after the last man left. The Space Race is almost done, but the field of lunar geology is exploding. Many Moon rocks are sent over to the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, more commonly known as Caltech.

The man in charge of these samples was Dr. Gerald Wasserburg, and he was an integral part of the moon missions, even if most folks have never heard of him.

Wasserburg was born in New Jersey in 1927, growing up during the Great Depression, rising antisemitism, and the foreshadows of WWII. By his own admission, he was not the best student, but he had a fondness for minerals and crystals- they provided a sense of beautiful order and control in uncertain times.

After serving in WWII, Wasserburg pursued his love of geology into college. He was a non-traditional student, a veteran taking classes with “friggin’ punk kids in class, 16-17 years old, who were actually a hundred times smarter than I was”. But Wasserburg learned and persisted, and eventually earned his PhD at the University of Chicago with Dr. Harold Urey.

We’ve met Urey and his proteges several times on this show. There’s Stanley Miller, who made the building blocks of life from scratch in Episode 20. Urey was also the mentor and eventual bane of Carl Sagan, working on Earth’s early atmosphere in Episode 28.

Wasserburg took a different path under Urey, learning how to date his crystals, how to tell the age of a rock. He took a position at Caltech and helped build the first digital dating machine in the world, 30x more accurate than anything else. This machine had a specific goal in mind: dating moon rocks. In honor of this mission, Wasserburg named his new machine the Lunatic. That name is not as crazy as it sounds. Luna is the Latin word for Moon, and lunatics were supposedly driven mad by it.

Wasserburg clearly had a sense of humor. For example, the Apollo 13 mission (yes, the one with Tom Hanks) never made it to the moon’s surface. The crew personally sent Caltech a signed photo saying: “Sorry we couldn’t bring back any rocks.” Apparently, that sign was on Wasserburg’s wall for years. In official published papers, his team would register as The Lunatic Asylum- I’ve never seen anything like that before. Which brings us back to 1974.

After years of hard work, the Lunatic Asylum announced the ages of NASA’s moon rocks. The team had two major conclusions. The first, we’ve already learned: the moon was formed 4.5 billion years ago, early January on the Earth Calendar. The second was weirder. All the moon rocks had been altered dramatically between 4.1 and 3.8 billion years old: February on the Calendar- something had remelted the rocks and reset their clocks.

According to the Lunatics, that event was a catastrophic barrage of asteroids, a series of sucker-punches from out of nowhere. But were they right?

Part 3: A Nice Model

Let’s put the Lunatic data into context.

In the beginning, Earth was pelted by asteroids on a scale we can’t even imagine- meteor showers every hour of every day. The modern Earth is much quieter, thank goodness. You might hear about a small asteroid punching though someone’s house, but that’s about it.

Clearly, the number and size of asteroid impacts has decreased. If you looked at a chart of asteroid impacts over history, it would look like a hockey stick - very high in the early days of January, quickly dropping down to modern levels by April (3 billion years ago), and staying low and flat until the modern day, December.

Here’s what the Lunatics proposed based on moon rocks: in February, around 4 billion years ago, the Moon was hit by an extra high-burst of asteroids, more than expected for the time. Imagine if the same thing happened to Earth today: things should be quiet, but then all of a sudden a plague of meteors hounds us for millions of years, only to disappear again.

The Lunatics called this disaster the Lunar Cataclysm. Modern researchers usually call it the Late Heavy Bombardment, since it happens later than you’d expect.

As usual on this show, the Late Heavy Bombardment is a subject of debate.

Let’s examine the data again. Remember, these rocks were collected from the Moon’s surface by the Apollo astronauts. Six missions visited the moon, each location hundreds of miles from the others. On one hand, it seems more than a coincidence that these spots have similar ages. On the other hand, it’s still only six spots, and the moon is a large place. Both sides would agree that more missions, more rocks, will help tell a more detailed story, whether or not Bombardment happened.

When we zoom out and look at the moon’s surface, many craters fall within the Bombardment window, but many others are even older, including the huge craters that make the Man in the Moon. Again, both sides look at lunar craters and tell you different stories.

How about other bodies in the Solar System? Mars and Mercury have many craters, some large, some small, some young, some old. As of 2024, the jury still appears to be out- there doesn’t appear to be a smoking gun for or against the Bombardment yet, though a larger consensus appears to be leaning away from it.

One final question before we go. Let’s assume that the Bombardment did happen, that around 4 billion years ago, a swarm of asteroids attacked the inner Solar System: the Moon, Earth, Mars, etc. Why would this happen? What changed?

The blame could be placed on the outer worlds.

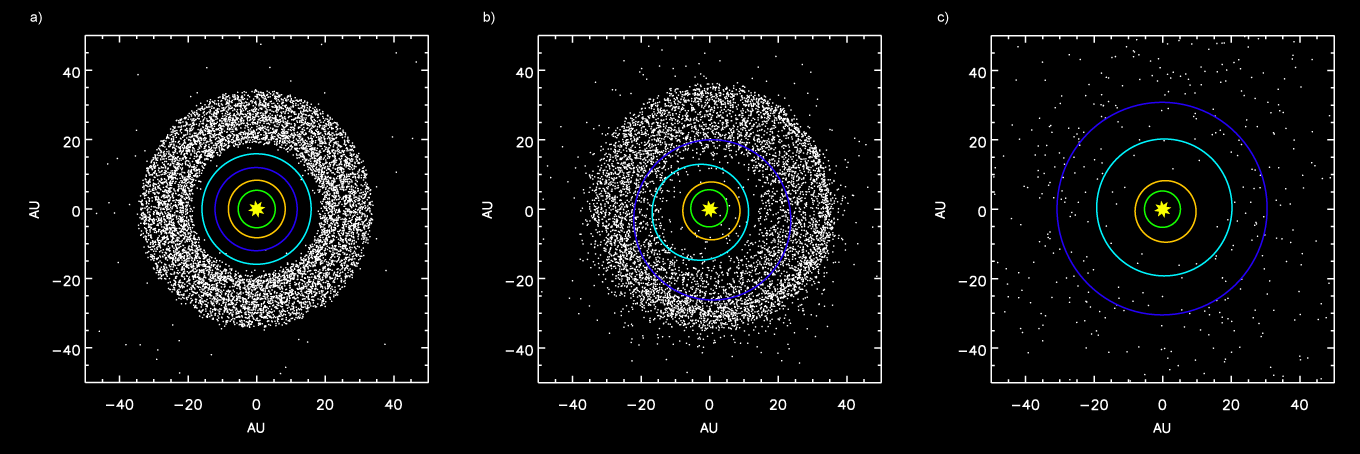

One variation of the Nice Model over time. Rings are the orbits of Jupiter (green), Saturn (orange), Uranus (light blue), Neptune (dark blue). White dots are asteroids, comets, and other smaller bodies scattered around the Solar System.

The four planets of the Inner Solar System are relatively small and rocky: Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. In contrast, the four outer planets: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, are much larger, more massive, and gassy. They have a lot of weight to throw around, and any change in their motion can have major effects around the system. We saw this in Episode 14, where Jupiter scattered icy comets across Earth’s surface, bringing life-giving water.

In 2005, a team of French researchers hypothesized that the gas giants were once much closer to the sun, and gradually migrated away over time. As they plowed their way outwards, the giants cleared out any remaining debris, shunting asteroids and comets in random directions, including their unsuspecting neighbors. Since the team was from Nice, France (that’s N-i-c-e), their model is called the Nice Model, which looks like the Nice model on paper. I find that amusing, but I’m easily amused.

The Nice model could explain many other features of our Solar System: the asteroid belt, and many objects beyond Pluto. But does it explain the Late Heavy Bombardment? First, we need to confirm that the Bombardment actually happened in the first place, but if it did, the Nice model would be a nice place to start.

Even though this story is unresolved, we’ll still bring it up in following episodes. Why should we care if the Moon has a few extra craters 4 billion years ago? Because if the Moon was hit, so was the Earth, and that could have major implications for life and the environment, but those are stories for another day.

Summary:

The Moon has millions of craters- each tell a different story. Some were formed at the very beginning of the Moon’s history, while others are still being made today. Here are the major themes we can follow: across the Solar System, crater size and frequency diminish over time. Our neighborhood has grown calmer since the wild early days of Season 1.

A major question in geology and astronomy is this: was the Moon shaped by an extra pulse of meteor impacts around 4 billion years ago? Gas giants like Jupiter might have unknowingly sent a barrage of material as they lumbered away from the sun. If so, life on Earth could literally have been dodging bullets early in its’ history. If not, don’t worry, there are still some serious impacts to come in later seasons.

Next episode, we’ll finish our Lunar Interlude by taking these ancient craters, filling them up with dark lava, and finally making the Man in the Moon.