Miniseries: The Oldest Rocks in Africa

Hello, and welcome to Bedrock, a podcast on Earth’s earliest history.

I’m your host, Dylan Wilmeth.

It’s been a while, but it’s good to be back behind the microphone. If you’ve been waiting patiently these past six months, thank you very much for sticking around. If you’re just joining us, welcome! For a full catch-up, check out the December update. Long story short, we’re picking up right where we left off- our mini-series on the oldest rocks on each continent. Then, in February, we’ll be diving back into the main storyline to finish Season 1: The Hadean Chapter, 4 billion years ago.

Our current mini-series gives a sneak peak into future locations from Seasons 2-5, so think of these episodes like teaser trailers. If you want to follow along at home, we’ll have geologic maps of each continent on our website: bedrockpodcast.com

The rocks in this series only cover 5% of the Earth’s surface, but represent the first half of Earth history, a time period called The Archean. To recap: we started with Antarctica, which only has small pockets of very altered rock. There might be a lot more, but it’s hidden under miles of ice. In contrast, Australia is an open book, with huge areas containing gold, iron, and Earth’s oldest fossils. Western Australia is a must-see for anyone studying Earth’s distant past. In fact, it was a major stop on my world tour last summer, but that’s a story for Season 3.

There’s only one other continent that goes toe-to-toe with Australia for ancient research, a landmass we will visit repeatedly, especially in Season 3. Break out your maps, it’s time to visit Africa.

***

Africa is Earth’s second largest continent, making up 20% of Earth’s land area. In 2022, one out of every five people lives in Africa, where humanity first evolved a few million years ago. But today, we’re looking at rocks that are billions of years old: January to June on the Earth Calendar, whereas humans don’t appear until December 31st.

I’ve been referring to Africa as a single unit, but in reality it holds more than 50 nations and an abundance of very different cultures. The same holds true for its rocks. The rocks we’ll see in Seasons 3-5 are spread across Africa, but only a few places still tell the tales of the ancient Earth. The main reason comes down to an ancient demolition derby.

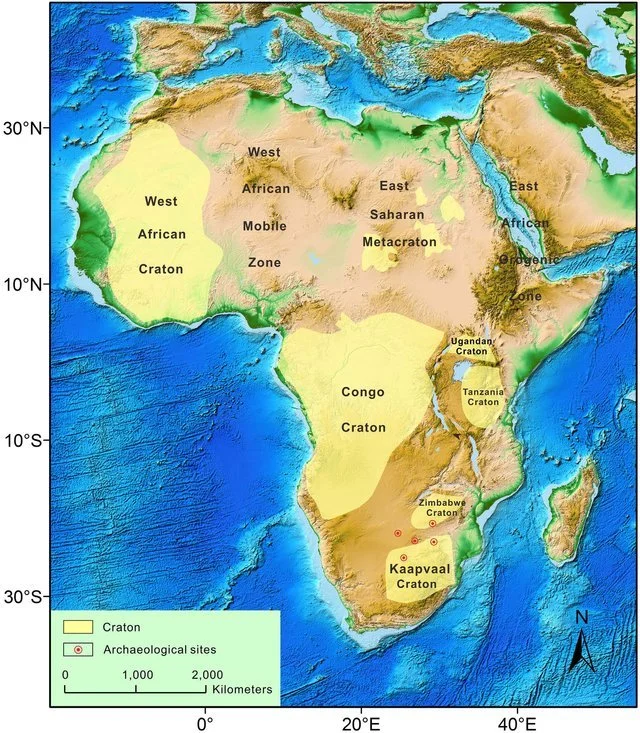

Archean cratons across Africa, highlighted in yellow.

The first landmasses on Earth were much smaller than Africa. They would have been the size of large islands like Madagascar- big, for sure, but not what we’d call a continent today. Instead, geologists call these areas “cratons”, as we learned in the Australian episode. These cratons floated around the early Earth like bumper cars, crashing into each other and fusing to form larger landmasses. When we look at every continent this series, we will find each has around a half-dozen cratons stitched together like a giant Frankenstein’s monster.

Every time these cratons smashed together, the rocks in between would become crumpled and deformed. For a good comparison, think about a monster truck rally- when two trucks smash into each other, their hoods usually fold, squeeze or crack. The same thing happened to many ancient rocks- they were caught in a continental crossfire. The best place to see this today is any mountain range from the Rockies to the Himalayas, where plates are slowly pile driving into each other. The mountains you see are forming in the same way as a crumpled car hood.

A few areas emerged relatively unscathed, like Australia’s Pilbara Craton last episode. These are the places that get the most attention from researchers- the rocks are the most pristine, considering everything they’ve been through. They have the best fossils and the best evidence for what Earth was up to billions of years ago.

In contrast, most ancient rocks have been warped and deformed by constant collision, like most of Africa. They are very useful for economic geology since they hold large deposits of gold, diamonds, and other precious materials. But trying to tell Earth’s surface stories using these battered rocks takes a lot more effort, or is sometimes just impossible. It’s not just Africa that has this issue- it’s the whole world. We’ll see it many times going forward- the older the rock is, the more likely it’s taken a geologic beating.

So, where are the best places in Africa to study the ancient Earth?

Before we talk about our prize locations, let’s briefly discuss one of the runners-up, for it’s an excellent example about how geology has shaped human history, for better and for worse.

Ashanti gold pendant from Ghana, 20th century.

Last episode, we talked about how gold rushes changed the economy of Western Australia in the 1800s. Now imagine if a culture found gold in their backyard a thousand years earlier. This is what happened in West Africa. Gold deposits were a cornerstone for centuries of trading empires, whose names live on in modern countries such as Ghana and Mali. The most famous of these rulers was Mansa Musa, supposedly the richest man in history. In the 1300s, shortly before Europe would tumble into the Hundred Years’ War and the Black Death, Musa made a holy pilgrimage to Mecca. On the way, he spent so much that he ruined the Egyptian economy by literally flooding the markets with gold. This gold was formed billions of years ago in the West African Craton, but Mansa Musa couldn’t have known that.

Centuries later, the same gold would draw the attention of European colonists, alongside spices, ivory, and human slaves. An abundance of natural resources can be a gift, but also a curse. This was shown more recently during the Sierra Leone Civil War from 1991-2002. The discovery of diamonds in the 1930s made a few people extremely wealthy while the mining areas remained underdeveloped, a major cause of unrest. During the war itself, revolutionaries seized diamond production, making hundreds of millions of dollars to buy weapons. Though the conflict is over, workers continue to be paid a few dollars a week, while the gems they extract sell for thousands or millions around the world.

Economics and warfare are not my strong suit, but both are deeply linked to where we find resources, especially those hidden within the ground. What I am more qualified to talk about is the scientific wealth of the Earth. West Africa does have some interesting rocks, but they won’t come until Seasons 6 through 9. The same is true for northern, eastern, central Africa and Madagascar - the oldest rocks are either too cooked or non-existent. It’s possible that there are some hidden pockets of decent material here, but more research has to be done first.

It’s finally time to talk about the crème de la crème- the best that Africa has to offer: Zimbabwe and South Africa.

Zimbabwe sits just northeast of South Africa, the same size as Germany or Montana. If you look at Zimbabwe from space, or on a satellite map in Google, you’ll instantly see something strange in the middle. Go ahead, take a pause from me blathering on and see if you can find it. You might have noticed a long thin line stretching north to south for miles like a giant knife cut. This is not a road or any nonsense about ancient aliens- this is the Great Dyke. The word dyke has many meanings- in this case, it’s a wall. On the ground, the Great Dyke is a straight ribbon of mountains splitting Zimbabwe in two.

So how was it made? On this show, we’ve talked a bit about magma chambers, large pockets of molten rock beneath Earth’s surface. These chambers cool into tough igneous rocks, forming mountain peaks like Yosemite or Sugarloaf Mountain. Sometimes, magma creeps into surrounding cracks, cutting through surrounding layers like a hot knife through butter. When these fingers cool down, they form long, thin ridges that geologists call “dykes”.

Zimbabwe is also one of the few nations to preserve Archean fossils. In the Australia episode, we learned about stromatolites, fossils of ancient microbial colonies, or just pond scum between you and me. Australian stromatolites are the oldest fossils, late March on the Earth Calendar. Zimbabwean stromatolites are a bit younger, around May to June. They are beautiful, but we won’t see them or the Great Dyke until the Seasons 4 and 5. So where can we find rocks from Season 3?

At the beginning of the episode, I said that Africa is the only place that goes toe-to-toe with Australia for ancient research sites. Then I spent five minutes telling you why most of Africa isn’t well-studied. The lion’s share of papers come from South Africa, especially about ancient life and ancient oceans. These rocks are the same age as any others in Africa- they just drew the lucky straw and escaped the tortured fate of their northern siblings. This lucky bumper car is called the Kaapvaal Craton, but we’ll keep calling it South Africa for now.

If you’re listening from Cape Town, Port Elizabeth, or Durban- I’m sad to say we won’t be reaching you until Season 9. The oldest rocks in South Africa are in the northeast, centered on Johannesburg, the largest city, and Pretoria, one of the capitals. The very oldest are in the east, just below Kruger National Park, and shared with South Africa’s smaller neighbor- Eswatini. To learn just how old these rocks are, check out my interview with Dr. Nadja Drabon, who has recently provided new dates and stories from South Africa. I’ve also had the pleasure of working four field seasons across South Africa, so expect a few tales of my own.

South Africa doesn’t have the oldest fossils in the world, but it’s a close second- 3.4 billion years ago instead of Australia’s 3.5- just a week’s difference in March on the Earth Calendar. In fact, as we travel forward in time, we will see many parallels between South Africa and Western Australia- when one has fossils or lava flows, the other usually does as well. They’re not twins, but they certainly appear related. Some researchers claim that the two were actually joined at the hip- two broken halves of an ancient continent. Others say there’s not enough evidence- I’ll let you decide as we go forward.

In either case, Western Australia and South Africa will be the main locations of Season 3, and major players through the rest of the series. South Africa will tell tales of rivers full of uranium, magma chambers the size of countries, and the largest meteor crater on the planet. But before we go, there’s one personal story I’d like to add.

In 2014, I made my first trip to South Africa for my Ph.D. research. Along the way, I made a few tourist stops to clear my head. One of these was the Cradle of Humankind- a World Heritage Site just outside Johannesburg. The Cradle is a series of caves which provided shelter for many generations of humans and their ancient ancestors, long before our species Homo sapiens. Around a third of all hominid fossils were discovered in these caves- the oldest around 3 million years ago. That might seem old, and it is old, but on the Earth Calendar, that is December 31st, 7 PM- five hours before the New Year’s bash of the modern day.

Stromatolite, 2.5 billion years old, Sudwala Caves, South Africa

While walking around the caves, I stopped dead in my tracks. I wasn’t looking at the bones on the floor, or at another uppity tourist, but at the walls. Not any cave art on the walls, but the walls themselves. The caves were made of limestone, and from floor to ceiling, the walls were built of thousands of domes made of tiny wrinkled layers. For most people, these would be pretty but unimportant patterns, looking more like cabbages or lasagna than anything else.

But with my experience, I knew that these were fossil microbial colonies, the stromatolites I mentioned last episode. These specific ones were 2.5 billion years old, mid-June on the Earth Calendar. As we’ll see in future seasons, these colonies will start pumping oxygen into the air and water, changing the Earth forever. It’s very poetic that the same lumpy rocks that unknowingly built the breathable world also unknowingly provided shelter for our ancient ancestors billions of years later, huddled around the first campfires. It sounds like something out of a science-fiction epic, but these are the stories we can tell through geology.

I’ve hyped up Australia and Africa a lot in this mini-series, but the other continents also have tales to tell, even if their episodes are a bit shorter. Case in point: our next stop, which is the fourth-largest continent, but only has a few scattered fragments of Archean rock left. It’s time to cross the Atlantic and see Africa’s mirror image in South America.

***

Thank you for listening to Bedrock, a part of Be Giants Media.

If you like what you’ve heard today, please take a second to rate our show wherever you tune in- just a simple click of the stars, no words needed unless you feel like it. If just one person rates the show every week or tells a friend, that makes us more visible to other curious folks. It always makes my day, and that one person could be you. You can drop me a line at bedrock.mailbox@gmail.com. See you next time!

Images:

Africa Craton Map: modified from Sun et al., 2016, Scientific Reports

Ashanti gold pendant: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pectoral,_Ghana,_Asante_(Ashanti),_early_20th_century_AD,_gold_-_Ethnological_Museum,_Berlin_-_DSC02269.JPG

Great Dyke: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Great_Dyke_of_Zimbabwe_ISS.JPG

Stromatolite: personal photo

Music: