Miniseries: The Oldest Rocks in Asia

Hello, and welcome to Bedrock, a podcast on Earth’s earliest history.

I’m your host, Dylan Wilmeth.

This mini-series covers the oldest rocks on each continent, plus some extra stories for flavor. These episodes give you a sneak peak into Seasons 3-5, so think of these episodes like teaser trailers. If you want to follow along at home, we’ll have geologic maps of each continent on our website: bedrockpodcast.com

The rocks on this series only cover 5% of the Earth’s surface, but represent the first half of Earth history, a time period called The Archean. Some continents have a lot of ancient rocks, some very few. This week, we head farther north than any other episode so far. Break out your maps, it’s time to visit Asia.

***

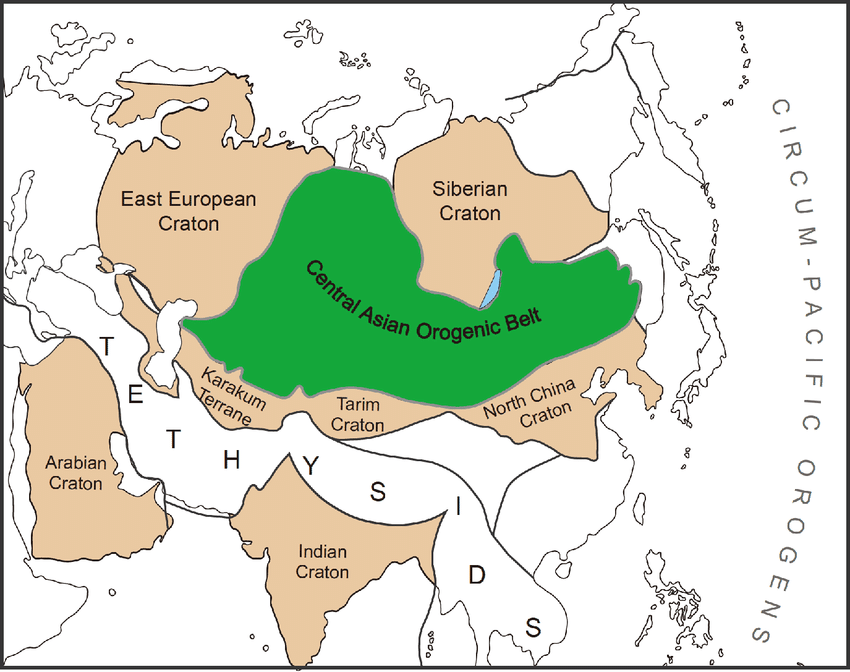

Simplified map of Eurasian cratons, from Xiao et al., 2020.

Asia is Earth’s largest and most populous continent. Thirty percent of all land is in Asia, and more than half of humanity lives there. Today, we will visit the three largest Asian countries: Russia, China, and India. In most other nations, Archean rocks are either buried too deep, or are eroded away. Instead, we’ll start our journey in the far north, just above the Arctic Circle. Welcome to Siberia.

Siberia covers 1/10th of Earth’s land area- it’s almost as large as Antarctica. If Siberia declared independence from Russia, it would be the largest nation on Earth. Yet only 35 million people live here, the same as California. So, when we visit lands that are remote by Siberian standards, that means something. Siberia has two slices of Archean rocks: the Anabar and Aldan Cratons. The Anabar Craton is a lonely forested plateau entirely north of the Arctic Circle. The highest point is a mountain without any name, and the largest town for hundreds of miles only has 2000 people. If you’re listening from Olenyok, welcome to the show. The Aldan Craton holds the coldest city in the world, Yakustk, with an average temperature of -8 C, or 18 F.

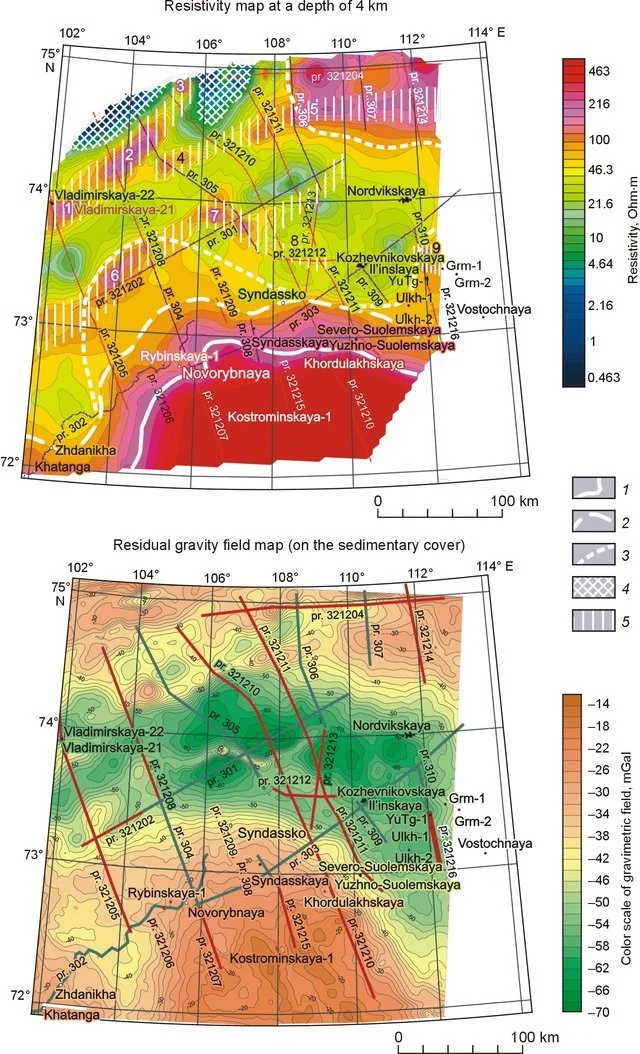

Furthermore, with pine trees covering most of the land and permafrost everywhere else, not many scientists have researched these Siberian cratons. Geology out here is like playing battleship- a hillside here, a riverbank there. Yet I can show you Siberian maps where Archean cratons stick out like sore thumbs, with clearly defined edges. How do we know?

Sub-surface maps in Siberia: top panel: magnetic fields, bottom panel: relative gravity. From Afanasenkov and Yakolev 2018, Russ. Geology & Geophysics.

The answer is physics- specifically gravity and magnetism. My apologies in advance to any physicists and especially geophysicists in the audience- this is a corner of the field I am not very familiar with, so forgive me for glaring errors.

First, gravity. When you think of gravity, you might picture planets swirling around the sun, or astronauts floating in space. Large objects have a larger gravitational pull than smaller ones, it’s why you can jump higher on the Moon than Earth- the gravity is less powerful. You might be surprised to learn that on Earth, different places have stronger and weaker gravity. If I buried a block of iron the size of a truck beneath your house, you would be pulled very, very slightly towards it . It’s not enough to make you feel heavier or stunt your growth, but it is enough for very sensitive machines to measure. Denser rocks have a greater pull from gravity, while empty spaces like caves have less of a pull.

Gravity helps map objects below our feet, but it only goes so far. It’s helpful to get a second opinion from magnetism. Let’s return to that block of iron beneath your house. The iron block has a much greater magnetic pull than a block of pure dirt. Most rocks have a little bit of iron inside, and are lightly magnetic. Again, it’s not enough to see- you could throw magnets at granite or sandstone all day and nothing would stick. But very sensitive machines could tell you that the granite is slightly more magnetic.

Combining gravity and magnetism, geophysicists can hunt for rocks no one has ever seen. Of course, it always helps to have a few stones at the surface just to be sure. In Siberia, these rocks are around 3 billion years old, April on the Earth Calendar. They’re not only rare, they have been cooked above 900 degrees Celsius, almost melted back into magma. Some rocks are slightly less baked, and we can even tell that some were lava flows or ancient seabeds. No fossils have been described yet, but if Siberia has any evidence for Archean life, the Aldan Craton would be the best place to start looking.

Our next stop is across the border in China. China has two large cratons with Archean rocks, helpfully named the North China and South China Cratons.

Most of the South China Craton is covered by younger rocks- where you could find fossil coral and dinosaurs. There’s one window where something much older peeks from below. Around the Three Gorges Dam in Hubei Province, a dome of ancient granite and gneiss old sticks out of the ground- this is the Huanling Complex. If you walk toward the center, the rocks get older. In a sense, it’s like hiking the Grand Canyon- if you pick a direction, you’re walking forward or backward in prehistory. The oldest rocks in the Grand Canyon are 1.8 billion years old, August on the Earth Calendar. The oldest rocks in the Huangling Complex are more than 3 billion years old, almost twice that age. The one downside is the small area, only around 40 miles in diameter.

Modern black smoker, Atlantic Ocean

In contrast, there are many Archean rocks exposed in North China, just outside the capital of Beijing. As with most Asian rocks, the North Chinese samples are too baked to find fossils, but there is a slice that tells a different story, one that makes a bit more money. Now if you’re worried I’ll repeat another anecdote about gold or iron, relax. It’s time for something completely different: copper and zinc. Our tale begins at the bottom of the ocean.

Imagine you’re in a submarine on the flat seafloor when suddenly you see a dark castle looming before you, with hundreds of belching chimneys. This is not the lair of sea giants, but a giant vent pumping out heat and minerals from magma chambers far below. Scientists call these chimneys “black smokers”. Their discovery is a fascinating story we will learn very soon on the main series.

So what does black smokers have to do with mining?

In the smokers, hot water dissolves minerals and metals from the surrounding rocks, rising in a rich chemical soup of sulfur, copper, and zinc among others. When this scalding soup shoots out into the freezing deep sea, the ingredients now freeze into solid forms again like metallic ice. This is how trace amounts of copper in the crust can become concentrated in one spot to mine.

Which brings us back to China. One of the largest copper and zinc mines in China used to be a black smoker, 2.5 billion years ago. The ancient seafloors are now rolling hills in the northeast Liaoning Province, close to North Korea. Similar mines are found in all the other locations from our previous episodes, too. They’re incredibly rich, but less extensive than iron mines- black smokers are very cool but relatively isolated features.

While we’re this close to Korea, a quick footnote. Rocks don’t care about political borders, stretching over into North Korea from China. People, however, do care about political borders and only a few papers have been written on North Korea. The rocks seem to be the same age and are probably cooked beyond fossil preservation.

If you’re a fossil fan like me, you might be a bit frustrated at this point. After the treasure troves of Australia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe, it’s been pretty slim pickings for Archean life. Most of the rocks this old are simply too cooked or too pressurized. Earth is a living, dynamic planet, constantly remaking itself. One of the costs of these makeovers is the destruction of old material. Sometimes to go forward, you must pick what pieces you want to change. All the change we’ve seen makes the surviving fossils all the more precious, which brings us to our last stop on our Asian tour: India. Before we look at India billions of years ago, I want to mention a much younger chapter first.

India’s wild ride for 70 million years

It’s December 20th on the Earth Calendar, 150 million years ago, well after the final season of this show. As we fly over ancient Asia, we see dinosaurs roaming Siberia, China, and Southeast Asia. But along the south coast, India is missing. So where is it?

Two episodes ago, I mentioned that Africa was built from a series of smaller islands. Last episode, I revealed that Brazil was another one of these islands. Spoiler alert: India was yet another attached piece, squeezed between Madagascar and Antarctica. 150 million years ago, all the southern continents were huddled together in a happy family called Gondwanaland. But the family couldn’t stay together forever. As the new Atlantic Ocean tore Africa and South America apart, India also broke away with gusto. Most continents travel at the same rate your fingernails grow, about half an inch a year. India was surfing at 8 inches a year, twenty times faster, closer to your hair growing.

For ages, India was an isolated speedboat cruising northward. But eventually, 50 million years ago, the inevitable collision happened. Neither India nor Asia could back down, so the only place to go was up. The seafloor between was shoved and squeezed into the tallest mountain range on the planet: the Himalayas. Fortunately for us Archean scientists, the rest of ancient India was left intact for us to study. India has five cratons, but we’ll only briefly cover two before wrapping up. Don’t worry, all of them will show up in later seasons.

First is the Dharwar Craton in the south. If you’re listening near Hyderabad, Chennai, or Goa, you are living near some of the oldest rocks on Earth. If you’re listening from Bangalore, you are living near some of the oldest fossils. Just like we’ve seen in previous episodes, these fossils are ancient bacterial colonies called stromatolites. The Dharwar fossils are only 2.7 billion years old (May on the Earth Calendar), but considering their rarity, let’s not be snobs about age.

Dharwar stromatolites look like small domes with wrinkled layers, resembling fossilized cabbages. But some are slightly different- imagine if you took a cabbage and squeezed it from a circle into an oval. That same squeezing has literally happened to these fossil colonies- not when they were alive, but long after. You are seeing fossils that are in the process of being erased.

Fossil stromatolites from the Dharwar Craton, northwest of Bangalore, India. From Khelen et al., 2019, Precambrian Research.

We’ve talked about beautiful samples and completely hosed rocks, but the reality is that most are somewhere in between. The most pristine samples give us the best clues about the ancient world, but this doesn’t mean we should turn up our noses at anything less than perfect. It’s possible you can overlook a diamond in the rough, such as out next stop: the Singhbhum Craton.

The Singhbhum Craton sits in east India, outside of Kolkata. The area is well-known for rich iron deposits- if you want to hear how those formed, check out the Australia and South America episodes. But for decades, the Dharwar Craton received far more scientific attention, at least from the fossil community. In the last few years that’s starting to change. Increasing evidence suggests that pockets of the Singhbhum Craton remain relatively pristine, even preserving stromatolite fossils. The age of these fossil bacteria is still being measured and debated, but even if the ballpark estimate is correct, they would be far older than their Dharwar siblings, 3 billion years or older, March on the Earth Calendar. If true, India would be placed on a pedestal alongside Australia and South Africa for the oldest life on Earth.

This is one of the breaking news stories of my field, and I’m excited to give you updates in future episodes. Speaking of which, it’s time to say goodbye to Asia and move down the road. Next episode, we head north of the Arctic Circle once again, as we visit the oldest rocks in Europe.

***

Thank you for listening to Bedrock, a part of Be Giants Media.

If you like what you’ve heard today, please take a second to rate our show wherever you tune in- just a simple click of the stars, no words needed unless you feel like it. If just one person rates the show every week or tells a friend, that makes us more visible to other curious folks. It always makes my day, and that one person could be you. You can drop me a line at bedrock.mailbox@gmail.com. See you next time!

Images:

Simplified Asian Craton Map: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338504140_Accretionary_processes_and_metallogenesis_of_the_Central_Asian_Orogenic_Belt_Advances_and_perspectives

Siberia Geophysical Map: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326429310_Application_of_electrical_prospecting_methods_to_petroleum_exploration_on_the_northern_margin_of_the_Siberian_Platform

Black Smoker: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6f/Blacksmoker_in_Atlantic_Ocean.jpg/640px-Blacksmoker_in_Atlantic_Ocean.jpg

India’s journey: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c7/Indian_subcontinent_drift-fr.svg/640px-Indian_subcontinent_drift-fr.svg.png

Dharwar stromatolites: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301926818303632?casa_token=f9hL0yXbBgUAAAAA:D_W4Uu6wsamdeKYWWjgqru4UfH11AKMtpxCMXXjzr8HcYC6MTFOY_KV_DKTHFSuerAnkTXPs