Miniseries: The Oldest Rocks in Europe

Hello, and welcome to Bedrock, a podcast on Earth’s earliest history.

I’m your host, Dylan Wilmeth.

This mini-series covers the oldest rocks on each continent, plus some extra stories for flavor. These few episodes give you teaser trailers into locations from Seasons 2-5. If you want to follow along at home, we’ll have geologic maps of each continent on our website: bedrockpodcast.com

The rocks on this series only cover 5% of the Earth’s surface, but represent the first half of Earth history, a time period called The Archean. Some continents have a lot of ancient rocks, some very few, such as our destination for this week. Break out your maps, it’s time to visit Europe.

***

The border between Europe and Asia over time at various points in history.

Europe is the second smallest continent, or is it? In this podcast, we’re using the 7-continent model of geography, but around the world, there are others. Technically, you could call North and South America one big continent, since they do touch in Panama. The same holds true for Africa and Asia- they meet up between Egypt and Israel. Whether you’re a lumper or a splitter, most folks would agree that the Americas, Africa, and Asia still form large areas that are almost completely separate.

The boundary between Europe and Asia is a different beast entirely. Most of this border is on dry land, and while there are differences on either side, a straight line can never tell the whole story. We have ancient Greek philosophers to blame for this, as they tried to match familiar and unfamiliar cultures with landscapes. The European border starts off normally around Greece, with the Mediterranean and Black Seas. But then eventually you run out of Black Sea to the East.

So the ancient geographers used the next best thing, rivers. Surely there’s another ocean just around the corner, right? Wrong. From the Black Sea, it’s about 2000 km of solid land straight north to the Arctic Ocean, and 6000 km east to the Pacific. 2,500 years later, and there still isn’t an official boundary between Europe and Asia. It’s a drunken line of mountains, rivers, and cultural divides, and it all depends on where you’re looking from. That being said, most people would agree on the broad strokes.

Starting where we left off at the Black Sea, we climb east across the spine of the Caucasus Mountains, separating Russia in the north from Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan to the south. Then we hit the Caspian Sea, Earth’s largest inland body of water. It used to be part of the global ocean, but was cut off when Africa, India, and other islands crashed into modern day Asia- to learn more, check out last episode. Is the Caspian actually a sea, or is it a giant lake? That’s a whole different can of worms to unravel, and we have enough on our plate.

Striking north, the Europe-Asia border broadly covers the Volga River and the Ural Mountain Range. The Urals strike straight north to the Arctic Ocean, dividing Russia into the larger eastern block of Siberia, which we covered last week, and the smaller but more populous European block.

So, now that we know the borders of Europe, where are the oldest rocks? Could you find Archean fossils in the Alps? Billion-year-old mountains near Berlin?

For most of Europe, the answer is: no, especially in the west.

Europe is by far the youngest continent, mostly built in November and December of the Earth Calendar, outside the range of this show. There are a few ancient scraps scattered around western Europe, but even these are relative newborns, October on the same calendar. We won’t see anything in the west between Portugal and Poland, Belgium and Bulgaria, until the final seasons of the show. Same goes for the British Isles.But it’s not all erased. Just like every other continent, Europe does have an Archean backbone, far to the east.

East European Craton regions, from Mezyk et al., 2018.

The East European Craton is one of the largest slices of ancient crust. The area covers Ukraine, western Russia, the Baltic States, and Scandinavia. It is divided into three zones: one is very well-known, the others are more mysterious. Let’s briefly start with our runners-up in the south and work our way north.

We start at the border between Ukraine and Russia. Geologists call this area Sarmatia, after a powerful group of nomads who lived here during ancient Greek and Roman times. Most of the ancient Sarmatian rocks are covered with younger rocks, forests, and grassy steppes. The main reason we know Sarmatia exists at all is thanks to scientists scanning the ground from above with sensitive machines. Consider these scans “x-rays” of deep rocks we can’t see- to learn more, check out the Asia episode. The pieces of Sarmatia that we have found are tantalizing, with rocks as old as 3.5 billion years, March on the Earth Calendar. Our old economic friends the Banded Iron Formations also pop up here and there, as we saw in Australia and South America. There is another mining story in the region- one that is much younger, but especially relevant today.

Sarmatia began to split apart around 350 million years ago, in early December of the Earth Calendar, forming a giant depression or basin. This is sometime after fish evolved, but still before the dinosaurs. In fact, animals and plants were just starting to make the great leap onto land. The new basin in Sarmatia was prime real estate, with warm oceanfront property for new forests to grow. To survive on dry land, these plants had to get tough and so, they evolved a brand-new material never seen on Earth before: wood.

Ancient coal forest, ~3

Wood is incredibly hardy and helps protect plants from the outside world. This was especially true for the first trees. They had just made a material that nothing else could eat. Bacteria, fungi, animals- all the things you see breaking down a log hadn’t developed the appetite yet. So when the first trees fell, they just sat on the ground for ages, rotting incredibly slowly. Then the next trees fell on top, and so on, huge piles of plants that slowly became buried in the ground. As the plants were buried deeper, they were pressure-cooked by Earth’s internal heat, eventually turning into jet black coal.

Eventually, bacteria, mushrooms, and insects evolved tough stomachs and could start munching away at wood. Thanks to these decomposers, a log in a modern forest doesn’t turn into coal- it’s eaten before it gets buried. For this reason, most coal on Earth is around 350 million years old- it was a golden age when trees couldn’t be touched. It also means that coal is a limited resource.

If we fast-forward in Sarmatian history, the buried coal was eventually pushed up to the surface, exposing the old basin once again. The basin is now exposed in the Donetsk region of eastern Ukraine, and is therefore called the Donetsk Coal Basin, or the Donbas for short. These names have appeared in the news for the past decade- coal has been a major source of economic and electric power for Ukraine since the 1800s, and it is one major factor in the current war with Russia. If you’re listening from Ukraine, this show wishes you the best of luck, and hopes you can stay safe.

Another slice of the ancient Earth lies across the border in Russia- it is called Volgo-Uralia, since it’s close to the Volga River and the Ural Mountains that we mentioned before. Unlike Sarmatia, no pieces of Volgo-Uralia are exposed- everything we know comes from subsurface scans, or drill cores plunged deep beneath the cities of Nizhny Novgorod, Kazan, and Samara, east of Moscow. These cores show that the rocks are just as old as Sarmatia, but have been extremely deformed, thanks to 3 billion years of collisions and mountain building.

In fact, the same mountains that bound modern Europe- the Caucasus and the Urals, are the same borders of the East European Craton. Despite the shade I threw at old geographers, they unknowingly were drawing the borders of Europe’s oldest slice. The final boundary is the Arctic Ocean, which brings us to the crown jewel of ancient Europe: Fennoscandia.

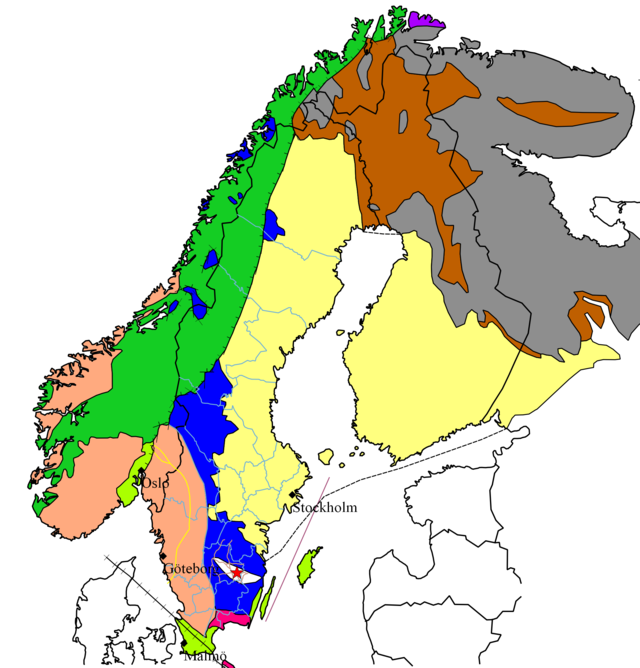

Various regions in the Baltic Shield

If the name Fennoscandia sounds like Scandinavia, you’re not wrong, and it’s time for another brief geography lesson. Scandinavia includes Norway and Sweden sticking down from the north, as well as Denmark, separated by the sea. Except for one lonely island, we will never talk about Danish rocks on this podcast- the old stuff is just across the water.

What about Finland? It’s right next door. Finland isn’t technically in Scandinavia- it’s separated by the Baltic Sea and the Finnish language, which is completely different from Swedish or Norwegian. In fact, Swedish is more closely related to Indian languages like Hindi or Bengali than to their neighbors the Finns. One thing that does unite Finland and Scandinavia are their ancient rocks, hence the name Fenno-scandia. The same rocks bleed over into northwest Russia, but the name’s long enough already. In fact, many scientists also call this area the Baltic Shield, since it’s focused on the Baltic Sea.

In fact, I’m just going to keep calling the area the Baltic Shield, but that geography dump wasn’t for nothing. The Baltic Shield will be a frequent location of our show starting around Season 4 and lasting all the way to the end. It’s good to know who the players will be. The rocks generally get younger to the west of the Baltic Shield. In broad strokes, Seasons 4 and 5 will be in Russia and Finland, Season 6 will be in Finland and Sweden, and Seasons 7 and 8 will be in Sweden and Norway.

Which means for this episode, we’ll make one final visit to the Russian frontier.

If you travel north from St. Petersburg, you will find the regions of Karelia and Murmansk, the Russian portions of the Baltic Shield. They are land of forest, tundra, and lakes- lots of lakes, more than 60,000 including the largest in Europe- Ladoga and Onega. These lakes actually help geologists map ancient landscapes- the shorelines provide excellent places to examine rocks at the surface. It’s nothing like the deserts of Western Australia, but it’s better than other locations in Europe. Another bonus of the Baltic Shield and is that Archean rocks are directly exposed at the surface here, rather than buried under younger material.

The oldest rocks here are granites around 3.5 billion years old. Most of the landscape here is granite, which comes in a variety of colors and patterns. Most have some mixture of pink and white crystals with minor amounts of black minerals. These crystals formed over thousands of years in magma chambers deep underground, and usually formed in a specific order. White plagioclase almost always crystallizes before pink potassium feldspars. In a way, it’s similar to how water freezes before beer or wine- the chemistry of each mineral defines when it’s solid or liquid. To learn more about this process, and about how we find plagioclase on the moon, check out Episode 9- The Great Gig in the Sky.

Finnish stamp featuring Rapakivi granite.

There’s one type of granite that’s especially beautiful and especially interesting for science. This granite is found around the world but was first described and named in the Baltic Shield, in Finnish rocks around 1.5 billion years old. It’s famous enough to have its’ own name in architecture: Baltic Brown, or Carmen Red. Geologists call it “rapakivi” granite, from the Finnish for “sandy rock”, since it breaks down easily.

How can tell if your granite countertop is rapakivi? You will see hundreds of small pink circles surrounded by white halos, huddled in a sea of black or gray crystals. This pattern tells us that pink feldspars formed before their white halos of plagioclase, something that shouldn’t happen in a magma chamber. It’s like someone switched the chapters around in your favorite book. Scientists are still debating how rapakivi granites form, but the most likely answer seems to be the mixing of two magma chambers. In any case, the results are gorgeous and dramatic, and you can probably find an example in your nearest city. Banks and monuments love using rapakivi granite- if you find an example, send me a picture at bedrock.mailbox@gmail.com.

The Baltic Shield will tell us many more stories, but it’s time to hit the road one last time. Next episode, we’ll round out our series with the oldest rocks in North America, which just happen to be the oldest rocks on Earth.

***

Thank you for listening to Bedrock, a part of Be Giants Media.

If you like what you’ve heard today, please take a second to rate our show wherever you tune in- just a simple click of the stars, no words needed unless you feel like it. If just one person rates the show every week or tells a friend, that makes us more visible to other curious folks. It always makes my day, and that one person could be you. You can drop me a line at bedrock.mailbox@gmail.com. See you next time!

Images:

Europe-Asia border: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boundaries_between_the_continents_of_Earth#/media/File:Eurasian_borders.jpg

East European Craton: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350728053_Structure_of_a_diffuse_suture_between_Fennoscandia_and_Sarmatia_in_SE_Poland_based_on_interpretation_of_regional_reflection_seismic_profiles_supported_by_unsupervised_clustering

Coal forest: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/61/Our_Native_Ferns_-_Carboniferous_Pteridophyta.jpg/640px-Our_Native_Ferns_-_Carboniferous_Pteridophyta.jpg

Baltic Shield: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/08/Overview_Baltic_shield.png/640px-Overview_Baltic_shield.png

Rapakivi Granite: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/79/Stamp_of_Finland_-_1986_-_Colnect_47103_-_Rapakivi_Granite_with_K-feldspar_and_plagioclase.jpeg/640px-Stamp_of_Finland_-_1986_-_Colnect_47103_-_Rapakivi_Granite_with_K-feldspar_and_plagioclase.jpeg