Miniseries: The Oldest Rocks in North America

Hello, and welcome to Bedrock, a podcast on Earth’s earliest history. I’m your host, Dylan Wilmeth.

We’ve arrived at the final episode in our mini-series on Earth’s oldest rocks. This series gives you a sneak peak into locations from Seasons 3-5, so think of these episodes like teaser trailers. If you want to follow along at home, we’ll have geologic maps of each continent on our website: bedrockpodcast.com

The rocks on this series only cover 5% of the Earth’s surface, but represent the first half of Earth history, a time period called The Archean. Some continents have a lot of ancient rocks, some very few. Our final destination has the largest, the oldest, and some of the most controversial rocks of the whole batch. Break out your maps, it’s time to visit North America.

***

As a continent, North America is perfectly average. It is the fourth most populous and the third largest on Earth. Most of its’ people and land are found in three countries: Canada, the United States of America, and Mexico. North America also includes Central America, and the many island nations of the Caribbean.

Like every continent we’ve met, Archean rocks are not spread equally across North America. We will never see any rocks from Central America or the Caribbean on this podcast- they formed far later in time. Mexico has a few small portions of ancient stone, but we won’t see them until the last season. The United States has some Archean rocks around Wyoming and the Great Lakes, but not very much considering the nation’s size. Other big countries we’ve seen have far larger patches: Russia, China, Brazil, India, and Australia. Which brings us to the second-largest country on Earth: Canada.

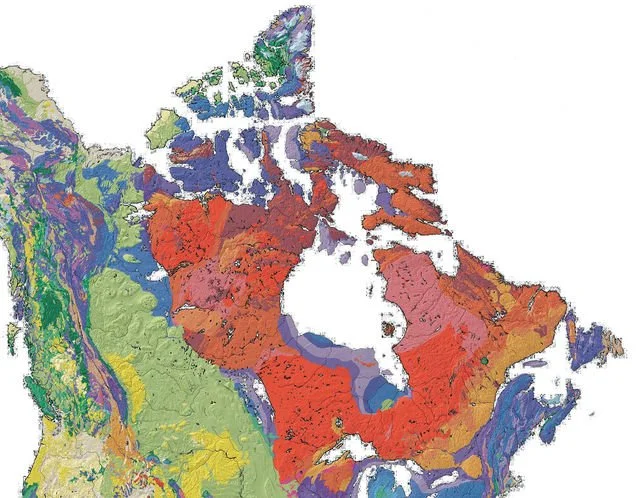

Canada contains the largest expanse of ancient rock on the planet, making up more than half of the country. This area is the famous Canadian Shield, which might ring a bell even if you’re not a geologist. The Canadian Shield forms a massive horseshoe around Hudson Bay, stretching from Quebec in the east over Ontario and Manitoba, then northwest to the Northwest Territories and Nunavut.

The Canadian Shield, highlighted in reds and oranges.

In this mini-series, we’ve talked about locations most people have never heard of, like the Pilbara, Kaapvaal, and Anabar Cratons. In my home country of the US, most people would recognize the Canadian Shield by name. It conjures images of vast pine forests with thousands of lakes filled with fish, moose, and loons crying out in the moonlit night. I’ve been very privileged to work in the Canadian Shield, and it’s one of my favorite places on Earth.

So why is it called a “shield”? Is Canada protecting the rest of North America from some ancient eldritch threat? A shield is simply a large area of old, stable rock. Canada’s oldest rocks form a wide, flat, round area… like a shield. But when you dig a little deeper, the Canadian Shield has some serious cracks in it. Like every other continent, it’s broken up into a half-dozen slices called “cratons”. We don’t have time to go over every single craton- we’ll leave that to the main series. Instead, I’ll show my personal bias and focus on what I consider Canada’s crown jewels: its’ oldest fossils.

Since we’re on the final episode of our world tour, let’s take a brief look back at where we find Archean fossils around the world. For a refresher, the Archean spans from 4 billion to 2.5 billion years ago, spring and summer in the Earth Calendar. The fossils themselves look pretty similar from place to place- wrinkled layers of ancient pond scum called stromatolites or “stroms” for short.

The oldest fossils on Earth are in northwest Australia, 3.5 billion years ago, with South Africa coming in a close second - both late March on the Calendar. The two nations also have many younger samples, providing an incredibly detailed history of early life. Flipping forward through the Calendar, we don’t see any new locations until May, around 3 billion years ago. Here, we finally see fossil bacteria from India and Zimbabwe… and that’s it. Adding Canada in this episode, the first half of life’s history is only found in five nations, possibly some in Brazil and Uruguay, though the jury’s still out. I call Archean stromatolites “fossil pond scum” out of affection, but in reality, they are rarer than diamonds, and far more important to our history.

Most of Canada’s Archean fossils are in northern Ontario and Quebec. These dig sites pop up in remote, isolated lakeshores and quarries- lonely islands in a sea of pine trees. About 2.9 billion years ago, these spots were actually islands in a huge global ocean. Canadian stromatolites are not the oldest, but they tell the story of a new type of rock, one that is intimately linked with life: limestone.

Giant limestone stromatolites from Ontario, Canada, 2.8 billion years old. Hat for scale. From Riding et al., 2014.

We first met limestone in Episode 2. Limestone is a sedimentary rock, which means it’s usually deposited in water, like sand or mud. Unlike sand or mud, which are tiny pieces of other older rocks, limestone forms from scratch straight out of the water. But limestone has a finnicky recipe, and not just any water will do. First, you need the right ingredients like calcium and carbon, as well as removing the wrong ingredients like iron. Then you need the right temperature- limestone prefers warm water over cold. Finally, the water can’t be too acidic, or limestone will dissolve away.

All these rules mean that limestone was pretty rare in Earth’s early days. We don’t see large limestone deposits until May on the Calendar, 3 billion years ago in Canada. So what changed?

First, we think that more new continents started to form around this time. More continents means more beaches and more warm, shallow waters just offshore, perfect places for limestone to grow. Life also played a part in these new sunlit seas. In the Australia and South American episodes, we learned that ancient bacteria learned how to harvest sunlight and make oxygen as a by-product, leading to the modern breathable world. This oxygen also turned iron floating in seawater into solid rust on the ocean floor, essentially scrubbing it from the oceans. These “scrubbing bubbles” helped clean the water for limestone’s finnicky recipe. Limestone is still forming today in warm, shallow waters- most famously in coral reefs. Modern reefs are teeming with fish, clams, sea urchins, and of course, coral. Three billion years ago in Canada, Earth’s first reefs were entirely made of bacteria. It was a very strange and alien world.

Archean limestone and fossils are also found much farther north in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut, but they are extremely remote and only a handful of papers have been written on these samples. This area is far more famous for another reason. Canada doesn’t have the oldest fossils on Earth, but it does have the oldest rocks on Earth.

As we did with fossils, let’s take a step back for context. In fact, let’s consider the podcast as a whole.

Before we took this side-trip last summer, we were wrapping up Season 1 of the main series. Season 1 covers Earth’s first chapter: the Hadean, from 4.6 to 4 billion years ago, January to mid-February on the Earth Calendar. There are no Hadean rocks left, they have all been ground into sand or melted into lava. Instead, almost every rock in this global miniseries is from Season 3 or later, after mid-March on the Calendar. But wait a minute, I skipped a bit there. What about Season 2?

Out of all the rocks we’ve seen around the world, this mini-series has only shown one location from Season 2. Kudos to you if you still remember it, I’ll give you a second to think. It’s the Napier Complex in Antarctica, way back six episodes ago. Let’s roll back the tape:

“These rocks are called the Napier Complex, and it’s around 3.8 billion years old, March 1st on the Earth Calendar. For context, Season 1 ends around mid-February, so these rocks are just around the corner. Even for researchers like myself, 3.8 billion is really old- there are very few places left from that time.”

Those other places are all in North America, the major stage for Season 2, including the oldest rocks on Earth.

A piece of the Acasta Gneiss, 4.0 billion years old

So, where and what are these rocks?

You’re standing on a riverbank in the Northwest Territories, far from any road and even farther from any town. These are the lands of the Tlicho people: tundra, scrubland, and sparse forests. The sky and river in front of you are deep blue, the shrubs are green and brown, but the rocks in between are black and white. These colors are sharply separated into zebra-stripes zig-zagging back and forth in great curves as large as a car. This is the Acasta Gneiss, 4 billion years old.

Gneiss, spelled g-n-e-i-s-s, is a metamorphic rock, which means it was once a totally different rock before being transformed deep underground by heat and pressure. Many of the oldest rocks in this mini-series are gneisses. I’ve been skimming over them because in short, they take the original stories of ancient Earth and change them like an overzealous editor. But we can still tell some stories if we look hard enough.

If we rewind the clock, the original rock of the Acasta Gneiss was not black or white or striped, but a uniform pale gray. This rock was tonalite- a cousin of the granite in your kitchen countertops. Like granite, tonalite is made from molten rock deep underground, and forms the backbones of ancient continents. If you want to learn more about how ocean crust turns into dry land, check out Episode 12: Scratching the Surface.

Does this mean that Earth had major continents 4 billion years ago? Probably not. Instead, the Acasta Gneiss tells us that North America started as a small volcanic island, similar to Iceland today. But from small things, big things grow. I’m only giving a short summary here, since we’ll be covering the Acasta Gneiss and its’ siblings in a few weeks.

There is one final place I’ll tease before wrapping up. The Acasta Gneiss has a very special place as Earth’s oldest rock, but age isn’t everything. Just ask Greenland.

Coming soon: Greenland, the main setting for Season 2.

Greenland is the world’s largest island, sitting almost entirely above the Arctic Circle, and is split between two worlds. Politically, Greenland is European- an autonomous part of Denmark. Geologically, Greenland is very much North American, with many pieces of the Canadian Shield stretching across the ocean. Most of Greenland is covered by ice sheets, so geologists are forced to work on the narrow rocky coasts. If this sounds familiar, there’s a reason.

We began this mini-series in Antarctica, looking at rocks 3.8 billion years old, squeezed between ice caps and the deep blue sea. We end in the Arctic Circle, looking at rocks the same age also resting between ice and tide. Both locations are incredibly remote, but while Antarctica is still obscure, Greenland is one of the most famous spots in early Earth research. If the Jack Hills of Australia was the superstar of Season 1, Greenland will steal the show in Season 2.

The difference between Antarctica and Greenland is how much they’ve been metamorphosed- in short, their cooking temperature. Antarctica’s rocks were heated above 900 degrees Celsius, or 1500 F, almost to their melting point. Greenland’s rocks were only baked to 500 degrees C. This is the difference between a gnarly zebra-striped gneiss, and rocks you can clearly identify as lava flows, seabeds, and depending on who you ask, maybe a few fossils.

But that’s a story for another day.

Epilogue:

Thank you for taking this grand detour with me. I started this mini-series in June 2022 to fill in my summer travels, and then life had other plans.

So where do we go from here?

Starting next episode, we finally return to the main series to finish up Season 1, the Hadean. We’ve run out of Jack Hills zircons to study- remember those little guys? But we’re still too early to reach the Acasta Gneiss we just learned about in Canada. So we’re entering a very murky but very important period of Earth history. It is in this foggy window that we will tackle one of the biggest questions in this series: when and how did life on Earth begin?

***

Thank you for listening to Bedrock, a part of Be Giants Media.

If you like what you’ve heard today, please take a second to rate our show wherever you tune in- just a simple click of the stars, no words needed unless you feel like it. If just one person rates the show every week or tells a friend, that makes us more visible to other curious folks. It always makes my day, and that one person could be you. You can drop me a line at bedrock.mailbox@gmail.com. See you next time!

Images:

Canadian Shield: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=canadian+shield&title=Special:MediaSearch&go=Go&type=image

Canadian stromatolite: modified from Riding et al., 2014, Precambrian Research

Greenland Fieldwork: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ef/Haproff.jpg/640px-Haproff.jpg